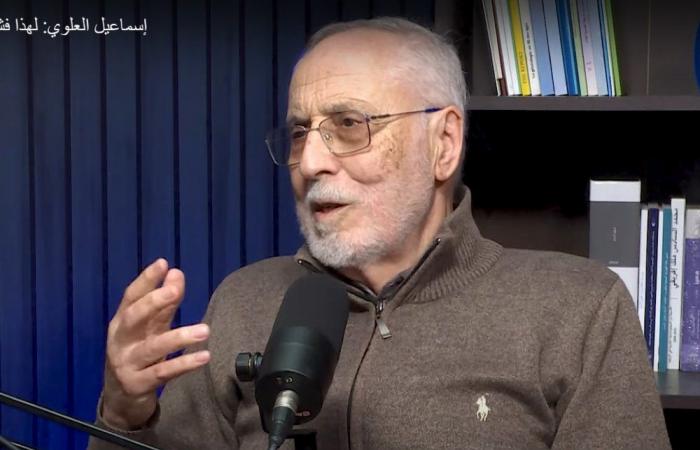

Seated against the microphones of The program “Educational questions”hosted by Khalid Samadiuniversity professor and former secretary of state for higher education, and Abdinasser Najidoctor of education and president of the Amaquen Foundation, Ismaïl Alaoui does not look like a bitter man. But behind the voice posed, the frank look, outcrops a still lively form of injury. Twenty-five years after having held the post of Minister of National Education in the first government alternation in the history of Morocco, he returns, without detour, at a pivotal moment and the trampled hopes that accompanied him.

Too wide reform for divided hands

The tone is calm, but the criticism is sharp, it continues: “We have never been gathered to develop a common vision. Everyone was advancing in their corridor, as if we did not belong to the same building. ” What the former minister regrets the most is “the absence of a captain. The Prime Minister should have decided. But in this mosaic of parties, everyone feared offend the other. Result: no line, no breath. “

The budget fracture or the impossible reform

Has the implementation of the pioneering school project has dismissed the principles of strategic vision and the legal framework in force? Has the Ministry of National Education really sacrificed four precious years of reform by focusing “only” on this project? These questions and many others were at the heart of the last report of the Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research (CSEFRS). The document, dedicated to the evaluation of this initiative, reveals that the objectives set have not been fully achieved. The project even seems difficult to generalize, due to the many obstacles that slow down its extension. Among these, we can cite the insufficiency of school infrastructure, the lack of educational support of teachers, as well as the regional disparities which amplify inequalities. In addition, the educational approach adopted, mainly focused on academic skills, is not unanimous. This situation raises a crucial question: how does the ministry intend to rectify this trajectory?

Despite everything, Ismaïl Alaoui Do not give up. He launched a management of school archives, militates for a National plan to combat illiteracydefends the place of Arabic in scientific education. But the brakes are multiple: administrative inertia, internal resistances, political indifference … Among the abandoned projects Alaoui deplores the creation of a real national service of Educational Archives. “There was not even an archive management in the ministry. We wanted to remedy it. But the managed manager did not believe it. The project has sunk into indifference. ” This memory remains lively. For Ismaïl Alaouieducational memory is a strategic issue. “I have seen fires destroy essential documents. I saw the memory of the school disappear in the pensioners’ granaries. It should scandalize us. ” And to conclude: “A nation that does not check its school is a nation that goes around in circles.”

Illiteracy: an abandoned fight

Another regret: the non-implementation of the national strategy against illiteracy. “We had designed a clear system: mobilization of teachers, financial incentives, creation of a national agency. Nothing has followed ”. Later, president of the strategic committee of this agency, he resigned. “I felt useless. I didn’t want to be an accomplice of an empty device. ” The situation today? “A quarter of Moroccans is still illiterate. And each year, 300,000 children leave school without a diploma, ”he deplores.

The education pact: a vision, not a force

In 2000, the Mithaq Al -atani (National Pact for Education and Training) is published. First structured strategic framework for the sector. But for the minister in place … it’s surprise. “We were not consulted. Not even auditioned. THE Pact was written elsewhere. ” He does not reject him. “I saw an honest attempt at it. But the text has never been transformed into law. He remained to the rank of promise. ” This floating between the ambition displayed and absence of constraint is for him a slow poison: “A country does not repair its school with symbolic texts. He needs law, budget, continuity. ”

Throughout this interview which lasts two hours, Ismaïl Alaoui Speaks without bitterness, but with sincerity that disarms. “I left the ministry in 2000. Two years, it’s little. Just enough to understand what we could have done. ” He says he has experienced episodes of exhaustion, tensions, lively frustrations. But he does not give up. “It is not failure that hurts. It is silence. The fact that no one turns around to understand. To learn the lessons. ” And to conclude: “We have not missed the school. We left it alone. ”

Today’s school: a disarticulated structure

What does he think of The current school ? The answer is frank: “She is an orphan. We changed the words, repainted the facades, multiplied the projects. But we have never resolved the heart of the problem: governance. The 2019 framework law ? An advance, he said, but too often bypassed. “Morocco has no vision problem. He has a translation problem. We theorizes a lot, we apply little. ” He also worries about the “silent” return of French in scientific subjects. “Arabic can teach physics, chemistry, mathematics. The linguistic argument is often a false pretext for the flight forward. ” For Ismaïl Alaoui, the stake remains. As long as the reforms are accompanied by stability or clear piloting, or real membership in the field, the Moroccan school will continue to go around in circles. “What we are going through today is the heritage of a school that has too often been half -reformed.”