In recent years, a worrying phenomenon has emerged in the field of public health: an increasingly marked increase in colorectal cancers in young adults. If, historically, this type of cancer was considered an elderly disease, it now affects individuals under the age of 50. In France, as in many other countries, this trend obviously challenges researchers and health professionals, because traditional risk factors such as poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, or smoking are not enough to explain this evolution.

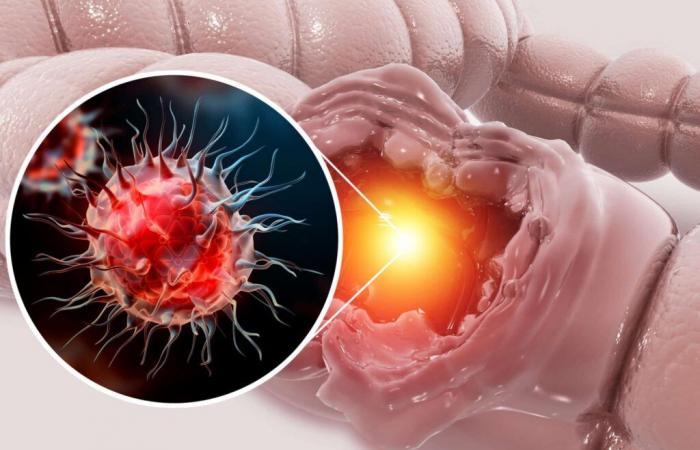

But a new scientific advance could offer an explanation: this explosion of colorectal cancers among young people could be linked to a toxin present in our intestine, produced by a common bacteria and so far often considered as harmless. This toxin is called Colibactin, and it could well be one of the key elements of this disturbing phenomenon.

Colibactin, suspect number one

Colibactin is a toxin produced by certain strains of Escherichia coli (E. coli), a bacteria that is naturally found in the human microbiota, especially in the intestine. Although most E. coli are harmless, some, like those carrying the PKS gene, are able to produce this toxin, capable of disturbing human DNA.

In a study recently published in Nature, an international team of researchers revealed that the Colibactin could be responsible for the formation of genetic changes directly linked to the development of colorectal cancer. Their research was based on DNA analysis of 981 colorectal tumors from patients in 11 different countries. By looking for specific mutations signatures, scientists discovered a striking correspondence between certain genetic alterations and the presence of colibactin.

The results of this study show that the genetic signature of Colibactin is much more frequent in young patients with colorectal cancers. In fact, the specific mutations caused by this toxin were 3.3 times more present in those under 40 than in over 70s, suggesting a direct link between toxin and the rise in early colorectal cancers.

An exhibition from childhood?

What is even more alarming is that this toxin could be present in our organism from the first years of life. Indeed, researchers suspect that exposure to Colibactin is not a phenomenon that develops in adulthood, but rather a process that could start from childhood.

Colibactin has the ability to cause DNA mutations in human cells by interfering with their genetic structure. If this toxin is present in the intestine for a long period – especially during youth – it could, over time, cause mutations in the cells of the intestine, thus increasing the risk of colorectal cancer earlier in life. One of the disturbing characteristics of this phenomenon is that the person concerned may present any obvious sign of lesion before years, making the detection of the problem very difficult.

This also raises the question of whether environmental factors, such as food, could play a role in activating these e strains. coli producing colibactin. Changes in the modern diet, rich in fats and sugars, could promote the implantation and proliferation of these pathogenic strains, thus increasing the risks.

Credit: ISTOCK

Credits: Shironosov/Istock

Towards targeted prevention?

Although this discovery is still recent, it opens up interesting perspectives for the prevention and detection of colorectal cancer among young people. The identification of the Colibactin as a potential risk factor could make it possible to develop new strategies to prevent the appearance of these cancers at an early age.

First of all, detection of E. Coli producing Colibactin could become a new early diagnostic tool. Indeed, a test to identify this toxin in the stools or the intestine could help identify people at risk earlier, before the appearance of the first symptoms.

Then, it would be possible to explore approaches to modify the intestinal microbiota of persons at risk, using probiotics or specific antimicrobial treatments to eliminate the pathogenic strains of E. coli producing colibactin. Another interesting track would be the use of treatments intended to inhibit the action of the Colibactin, so as to limit its mutagen impact.

Finally, colorectal cancer screening recommendations could be revised to integrate earlier examinations, especially for young adults with risk factors. Currently, systematic screening generally only starts from the age of 50. If the Colibactin is indeed a risk factor, it would be relevant to lower this age limit.

A silent revolution in cancer research

This discovery represents a turning point in understanding the causes of the increase in early colorectal cancers. It invites us to rethink the way in which the intestinal microbiota can affect our long -term health, and in particular to reflect on its role in the triggering of early cancers.

Although research is still at a preliminary stage, the highlighting of the possible role of Colibactin offers promising tracks for future research and treatments. This could also transform colorectal cancer prevention strategies, allowing us to identify risks from childhood, not in adulthood.

As one of the main researchers in the study points out:

“We knew that colorectal cancer increased among young people, but we did not know why. Now we have a track. »»

It is therefore possible that, in the near future, this track leads to concrete solutions, making it possible to slow down this silent epidemic.